|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Searching for the Pagan Goddess

The Universal Man is also a Woman

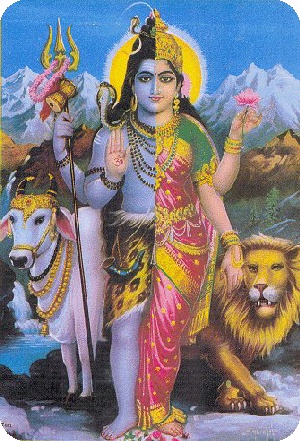

Editor's Note: For many generations women having been looking for a spiritual bond with a goddess. Modern Christianity is too full of patriarchal hypocrisy and this has left many women looking for alternatives. Ancient Judeo-Christianity was very much a pagan religion when it was in its infancy and included not one but two gods, equal halves of a whole (similar to Shiva and Shakti in the Hindu faith, Odin and Frigg of the Norse faith, Zeus and Hera in the Greek faith, etc). Indeed this duality of male and female halves was common to nearly all ancient religions. Christianity separated itself from the rest as it evolved into a new religion with only one god. By Marta Maslej - September 2009. “The moon is my mother. She is not sweet like Mary…” (Sylvia Plath) The progression from Paganism into modern day Christianity traced a defeat of the goddess, who very graciously [and femininely!] bore many transgressions against her. Even prior to the introduction of monotheism, she was being replaced by male deities, usurped by her own sons and the span of her reign dissipated in increments until all her power eventually seeped into the figure of a single, male God. In ancient Israel, a monotheistic faith coincided with the upholding of a patriarchy. The people were obligated to put all their spiritual, social, and political eggs into one basket. They abided by the strict divine order to place no other god before the One that delivered them from slavery, granting them their freedom. This, of course, had important implications in other areas of life. A strict loyalty to one God was also associated with an exclusive loyalty to one’s father, one’s husband, one’s country and its political and social ideals. In every corner of life, it seemed that there stood a jealous patriarch to ensure a complete and unconditional devotion to his needs and demands. This attempt to centralize control into masculine hands nevertheless seemed rooted in a fear of the other- other men, other countries and their systems, other gods- which translated into more general fears of the dark, the obscure, the primal and ultimately, the feminine. There was no alternative to offset this masculine tip on the scale. In pagan societies, a plethora of gods were available to display and model a variety of gendered characteristics. Goddesses were alluring, gods were strong and virile; the powers of these presences were in a constant flux and the resulting tensions and conflicts reverberated in the material world. In the bible however any such distinctions were eradicated. The depictions of ordinary men and women failed to represent a distinct femininity. This egalitarianism seemed ideal yet it was limited to the way gender was depicted; where women did not differ from men in character, they certainly suffered profoundly when it came to status. And ultimately, this lack of a distinct womanhood led to an accepted, masculine norm.

One role that the woman retained due to her biological capacity was her identity as a mother. The biblical mother was always loyal and eternally protective of her offspring and this was still justified in relation to a larger, more universal purpose: God’s wish for her to be fruitful. Mary of Nazareth’s fame comes precisely from this role; she is forever destined to either lovingly clutch an infant Christ at her breast or keel in anguish over his lifeless body. Throughout his tumultuous childhood and despite the allegations brought upon him in his adult years, the model mother stood by her child’s side in a sort of reversal of the paternal loyalty described above. In this case, it was still always the woman who remained loyal to the man, her son, for reasons that were beyond her. While procreation was the only power available to the female, it was still limited. The woman contained the necessary resources to develop life and yet, the male God remained the artist who formed the being in her womb, cared for it during its development and determined its eventual fate in the world. This was also the source of her association with nature. Like the earth provided the setting and nourishment for a seed which happened to fall from a nearby tree, she too was the vessel that temporarily sheltered a life that was never really hers to begin with. The introduction of Christianity also saw a distinct suppression of sexuality that once served an important purpose in the ancient world. More specifically, sexuality was in the domain of the goddess and associated with agricultural fertilization and the continuing survival of the cosmos. Unfit for a pure, paternal deity, this female power became useless and even threatening, and had to be domesticated or contested. As a result, the virginity of women was elevated with a feverish obsession. Religious literature overflows with stories of nuns as they denied their basic physiological and carnal needs to the point of martyrdom. Avoiding the satisfaction of the body became the ultimate method of acquiring a transcendental, male spirituality.

The visions of women in the Medieval Period were preoccupied by these notions. St. Leoba, in her quest for perfection in monastic life, dreamed one night that she was pulling a string of yarn through her mouth. It came from deep within her stomach and formed a ball in her hands. She was advised that this vision foreshadowed the wise counsel that would later come from her heart, and yet, the main feature of her vision was the explicit removal of something from her body. In her dream, St. Leoba purged her insides: her basic needs as represented by the intestinal string and her womb when the clump of string eventually formed a ball. Evidently, the ideals of her society required this disturbing extraction of a corporeal femininity in order for the spiritual realm to be accessed by a female. In their quests for vision, medieval women were at a clear disadvantage. Because they had internalized these masculine ideals, they functioned as their own obstacles by conforming to the very standards that suppressed them. The modern woman experiences a similar ambivalence, further complicated by her society’s widespread disillusionment with traditional religion. Any reference to the divine becomes ironic in a world where we are guided by ticking clocks, ringing phones and the accumulation of goods while the Lord is neatly compressed into an hour-long slot at the end of the week. The spiritual realm is no longer complementary to our physical existence. Rather, it has become a stark juxtaposition. And alas- the removal of an immanent, corporeal spirituality has placed the Western world in a bind. Like St. Loeba, we have drawn the divine string from deep within ourselves and placed it out of reach, with no idea how to reel it back in.

“Pure? What does it mean? This modern cynicism becomes an important issue for contemporary artists. We can attribute much of poet Sylvia Plath’s controversial status, for example, to her attack on religious figures in her writing. She comments on the dwindling ability for traditional, patriarchal faith systems to function realistically in modern society. In her poems, the deities are featured in a geriatric state. Old and overweight, they are unable execute their duties. The surrounding army of angels and cherubs are equally useless, pink things that float around the Virgin and her baby. Plath also spares no mercy on the females that inhabit the Christian landscape. In her writings, she condemns the Virgin Mary for her insignificant role, reducing her to a womb that bears Christ and later, a puddle of tears that mourns him. Perhaps in her own harsh way, Plath recognizes the sad reality that these structures, belonging to the spiritual world of myth and imagination, are so far removed from our current existence, that we have no idea what to do with them. Pretty and ornate, they become souvenirs from an ancient past and now, they sit on the shelf, gathering dust.

“I am mad, calls the spider, waving its many arms. And yet, as useless and even contradictory as these religious figures are to Plath’s quest for inspiration, creativity and wisdom, they still exorcise their authority over her work. The alternate view of the male deity in her poetry is no less negative; she represents Him as the vengeful sadistic God, who preys on humans and devours them with his rage. In Plath’s work, God is conflated to many things. He is the animalistic predator, the vengeful father, the abusive husband, and his debilitating authority spills into all areas of her life. Again, the monotheistic, all-in-one paternal loyalty rears its head.

“You do not do, you do not do Any more, black shoe In which I have lived like a foot For thirty years, poor and white, Barely daring to breathe or Achoo. Plath takes her controversial stance on formal religion further by instigating a verbal attack against the patriarchal traditions that oppress her. In her poetry, she rewrites the original biblical text according to modern and feminist ideals. The society that she writes for no longer desires somber, didactic accounts like those of the male resurrection. Her audience is bent on consumerism, entertainment and sex, all of which the speaker fulfills in the poem above. After rising from the dead, Lady Lazarus playfully reveals her wounds to a crowd, while administering a charge. Where Christ sacrifices his life for the redemption of humanity, her rebirth is meant for the redemption of womanhood. By rewriting the story, Plath has prophetically and perhaps even inconspicuously stepped into a territory of gendered spiritual warfare with a surprisingly fresh take: if she cannot change her gender to access the masculine, spiritual realm, she will instead modify the spiritual realm enough to fit her needs as a modern female.

And yet, Plath was not the first to engage in this sort of thought. Many females before her, in muted ways, searched for feminine methods of acquiring vision. The goddess’s diminishing role had left them alarmingly few options. As a result, these visionaries took the characteristics that were either unavailable or undesirable to the male deity and used them as distinctly female mechanisms for achieving spirituality. By doing so, they also resurrected important components of Paganism; primarily, these women concerned themselves with the body, sexuality and more importantly, the womb and its connection with the earth. An adoration of the female womb would have been considered heresy in the Middle Ages nevertheless it appears as a constant symbol in its art and writing. Examining Medieval depictions of the female reproductive system, scholars have found evidence of crucifixion iconography. This recognition of the divine in the body points to an immanent, corporeal spirituality. It also emphasizes the female’s integral role in the incarnation; while Mary’s body nurtures a human Christ, it is also her womb that harbors a divine presence.

“But when the time came for you to be delivered, your labor pains were so great that your holy sweat was like great drops of blood…Ah, Sweet Lord Jesus Christ, who ever saw a mother suffer such a birth! For when the hour of your delivery came you were placed on the hard bed of the cross … and your nerves and all of your veins were broken. And truly it is no surprise that your veins burst when in one day you gave birth to the whole world….” (Marguerite) Several visionaries in the Medieval period further unravel this notion. Marguerite of Oignt imagines a maternal Christ. Strained with suffering, he labors to give birth to the Church and provide humanity with a new, pure life. “It was our stomachs-not brains or hearts- that God endowed with the capacity to comprehend the cosmos, and vice versa- the cosmos was nothing more than a giant stomach passing cosmic matter through us while we lived on earth…” (Hildegarde)

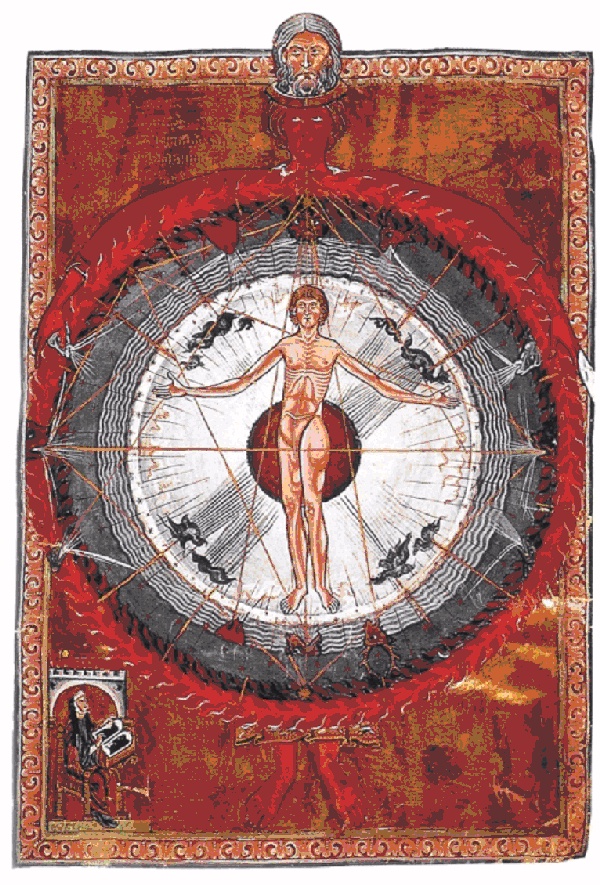

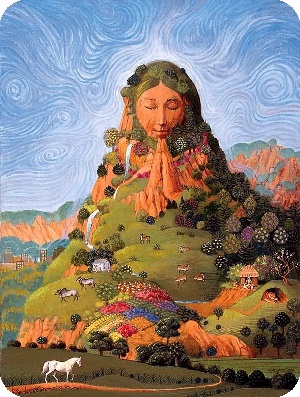

In no other Medieval vision is this notion of a maternal deity so concretely apparent than in Hildegarde of Bingen’s work The Universal Man. In it, the human figure occupies a central space, enclosed in a circular, womb-like universe. Using her art as a tool, Hildegarde revives notions of a corporeal spirituality and immanence. For her, humanity is created from the same material as the cosmos and naturally, the key to both creation and creator are in the human and not outside of it. Hildegarde also adds a feminine component to the dominant male deity; in her image, the elderly bearded God is attached to a more subtle female and her swollen body. While the male creator still maintains his power over the female goddess that bears his creation, The Universal Man remains a powerful suggestion of a feminine deity. Hildegarde also reclaims the importance of sexuality, not only to the continuation of the cosmos, but for the development of a spiritual awareness. The figure in the centre is androgynous; it transgresses boundaries of gender. More specifically, it represents the physical union of the male and the female. According to Hildegarde, the human spirit is released through sex to enter into universe’s eternal and pervasive harmony. As the figure in her image extends its arms to fire and air, the human also has the potential to comprehend the divine in the natural elements. Or, in a more secular sense, he or she can tap into the cosmos’s gifts of inspiration, creativity and wisdom through a physical connection with the other. Here, the pagan goddess of sexuality is at last awakened through symbol and representation. “The majority of dream and of ordinary vision is vision of the womb. The brain and the womb are both centers of consciousness, equally important.” Poet and theorist, Hilda Doolittle draws from the ancient traditions which Hildegarde accesses and defines them more concretely. According to HD, vision comes from the creation, possession and expulsion of life into the world. While she acknowledges the knowledge that comes from the brain, the intellect or a higher consciousness, which is inherently a masculine ideal, she presents an equally powerful feminine substitute. The potential to create within the womb becomes the woman’s divine power.

“the ecstasy comes through you

What, according to some theorists, separates man from beast is an excess of creative energies, the power of mythic imagination. They assert that myth lies in the DNA of the human psyche and is passed on throughout generations. The mythic imagination is our innate power to discern the functioning of the cosmos and the play of divine presences within it. By implication, the responsibility to create, develop and ultimately expel this mythic power is then an exclusively female task. Her body is a vessel for a rapidly growing bundle of nerves and flesh, and somewhere deep within each cell, the new organism also holds this excess of creativity and imagination, apart from its tiny material existence. This is how the womb, as the carrier of this developing consciousness, is also a centre of vision. This, of course, is not a new idea. Rather, it is an ancient notion reinvented. According to Pagan traditions, the womb of the primeval mother, the maternal goddess, is the source of creation. She is also linked with every woman who, as an individual site of growth and birth, can manifest this primordial mother within herself and transmit her throughout time and space. This is precisely HD’s intention: as a poet, she uses words to create analogies and links between all things. In her theory however, the womb is the closest analogical link between women now and the generations of women that came before her. Disillusioned with the notion of a single, transcendent creator, Sylvia Plath continues on this quest to revive a vast maternal tradition. In her poetry, she describes her frustration when, attempting to conjure a single, divine presence, nothing comes. She only becomes successful in the poem, “The Plethora of Dryads”; her creativity and inspiration manifests in an outbreak of diverse spirits and gods and consequently, an acceptance of both paternal and maternal deities.

“The moon is my mother. She is not sweet like Mary… It is not so simple for Plath to adopt an alternate spirituality. Her poetry depicts a struggle to sort out her beliefs. Slowly, she progresses from an attempt to reconcile her own ideologies with those of the Church to more ancient alternatives. She searches for a divine mother and she is pointed towards a powerful, natural symbol of the matriarchal spirit; it is not long before the stiff faces of the effigy are replaced by the wild, ever-changing phases of the moon. Tired of outdated icons and the ancient religious souvenirs gathering dust on her internal shelves, she turns outdoors to a maternal deity which resides in the skies and contests the frozen perfection of traditional iconography.

While Plath still harbors a nostalgic longing for the traditional figures she has known all her life, she realizes the sweet domesticity of Mary is an illusion. It serves a patriarchal disguise, distracting her from the matriarchal consciousness. Yet, even this maternal deity is not just an entryway into a patriarchal spirituality. It is a presence in its own right, contesting the supremacy of its male counterparts. The female is no longer made by man or out of man. She becomes the central figure in life and creation. The emphasis on the body and the womb, by implication, associates the female with the earth. Traditionally, this connection with the material world had to be severed in order to move beyond it and reach a distant God in some alternate realm. Female visionaries however have embraced their connection with the earth as a method of attaining spirituality. In the pagan world, animals, humanity and divinity were considered to exist along a continuum, with gods mediating between the natural environment and the creatures that lived within it. The onset of monotheism however shifted this model in important ways. At once, it was human behavior that determined God’s actions; the natural environment became a mechanism through which he displayed his emotions, his pleasure, or his displeasure with what he observed. Ruling over all things, he manipulated them as he saw fit. In this regard, the masculine God exercised his authority over a female earth and she became either a dependant child, in need of humanity’s mercy and care, or a wild, destructive force. It is not by coincidence that this view of the earth also corresponds to Western, gender binaries. The view of women can be divided into the same extremes: helpless and unassuming or irrational and witchlike. And yet, the notion of an intimate connection to nature as a form of spiritual idealism appears as well in Christianity. It can be traced back to the biblical account of the fall from Eden. Until he ate from the Tree of Knowledge, man once lived in perfect communion with the natural world, completely unaware of his own ego and its distinction from the universe. St. Umilta of Faenza acknowledges this when she sorrowfully laments, “I was planted in charity, but now I have been pulled out of that ground, roots have been dried up”.

Hildegarde of Bingen similarly advocates this bond with nature as a method of communicating with the cosmos. She notes that because every creature is bound to the next, we each form part of a delicate ecosystem. Like the womb becomes the analogical link between all women, the earth is similarly the link between all creatures. Once again, a maternal symbol becomes a unifying, cosmic principle. Plath makes a similar vow to surrender her senses to nature. In her early poetry, she attempts to reach beyond nature to attain an ideal and perfect form, which proves to be unsuccessful, even detrimental to her creativity and inspiration. She ultimately concludes that a one-dimensional heaven requires a flattening of the soul. For Plath, perfection tamps the womb, reducing vision. In this way, she submits herself to an ancient Gnostic principle: to experience the divine through nature, not matter how disorderly or imperfect it appears, and not using a cold, scientific rationality. Still, it is far too luring to fall into these romantic notions of nature, carnal idealism, and the sweet and mysterious workings of the womb. These are all exotic stereotypes of feminine charm, her natural connection to nature and her ability to create life. While they are all valid alternatives to masculine ideals, they are still just that- ideals that can be harmful when elevated beyond their means or applied rigidly and universally across all women, all cultures and systems of faith. Clearly, viewing the womb and a primal connection to nature as inherent and exclusive ways of attaining vision has problematic implications. Nevertheless, it is worth noting the boldness, innovation and vision of these women. Disillusioned by their diminished role in spiritual matters, they have fought to restore and reinvent ideas that place them in the centre of creation, inspiration and life. These ideas, and those of others to come, will continue to enrich the current religious landscape in hopes of one day re-bridging the gap between the material world and its lost spiritual counterpart.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||