|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

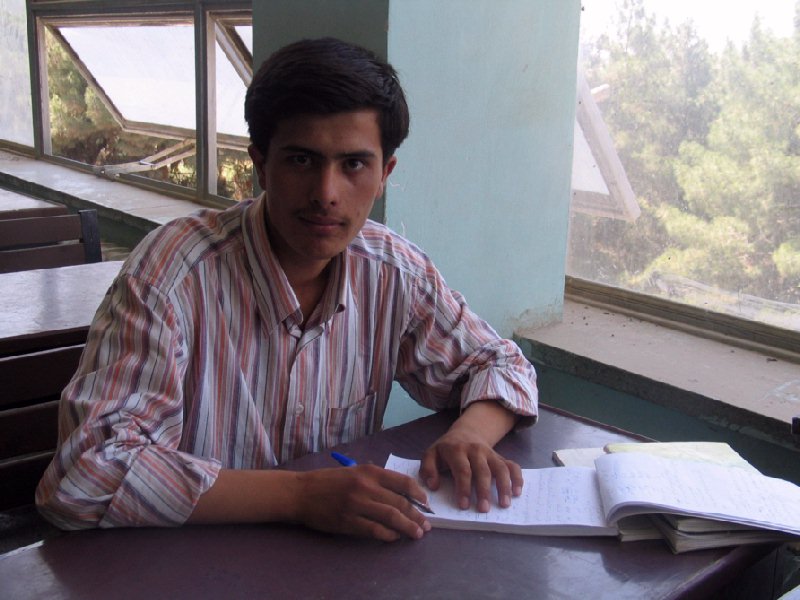

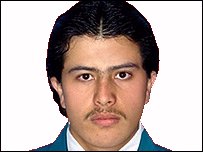

Sayed Pervez Kambaksh, Afghan who dared to read about women's rights

Afghan who dared to read about women's rightsFebruary 2008. A young man, a student of journalism, is sentenced to death by an Islamic court for downloading a feminist report from the internet. The sentence is then upheld by the country's rulers. This is Afghanistan – not in Taliban times but six years after "liberation" and under the democratic rule of the West's ally Hamid Karzai. The fate of Sayed Pervez Kambaksh has led to domestic and international protests, and deepening concern about erosion of civil liberties in Afghanistan. He was accused of blasphemy after he downloaded a report from a Farsi website which stated that Muslim fundamentalists who claimed the Koran justified the oppression of women had misrepresented the views of the prophet Mohamed. Mr Kambaksh, 23, distributed the tract to fellow students and teachers at Balkh University with the aim, he said, of provoking a debate on the matter. But a complaint was made against him and he was arrested, tried by religious judges without – say his friends and family – being allowed legal representation and sentenced to death. The Independent is launching a campaign today to secure justice for Mr Kambaksh. The UN, human rights groups, journalists' organisations and Western diplomats have urged Mr Karzai's government to intervene and free him. But the Afghan Senate passed a motion yesterday confirming the death sentence. The MP who proposed the ruling condemning Mr Kambaksh was Sibghatullah Mojaddedi, a key ally of Mr Karzai. The Senate also attacked the international community for putting pressure on the Afghan government and urged Mr Karzai not to be influenced by outside un-Islamic views. The case of Mr Kambaksh, who also worked a s reporter for the Jahan-i-Naw (New World) newspaper, is seen in Afghanistan as yet another chapter in the escalation in the confrontation between Afghanistan and the West. It comes in the wake of Mr Karzai accusing the British of actually worsening the situation in Helmand province by their actions and his subsequent blocking of the appointment of Lord Ashdown as the UN envoy and expelling a British and an Irish diplomat. Demonstrations, organised by clerics, against the alleged foreign interference have been held in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif, where Mr Kambaksh was arrested. Aminuddin Muzafari, the first secretary of the houses of parliament, said: "People should realise that as we are representatives of an Islamic country therefore we can never tolerate insults to reverences of Islamic religion." At a gathering in Takhar province, Maulavi Ghulam Rabbani Rahmani, the heads of the Ulema council, said: "We want the government and the courts to execute the court verdict on Kambaksh as soon as possible." In Parwan province, another senior cleric, Maulavi Muhammad Asif, said: "This decision is for disrespecting the holy Koran and the government should enforce the decision before it came under more pressure from foreigners."

UK officials say they are particularly concerned about such draconian action being taken against a journalist. The Foreign Office and Department for International Development has donated large sums to the training of media workers in the country. The Government funds the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) in the Helmand capital, Lashkar Gar. Mr Kambaksh's brother, Sayed Yaqub Ibrahimi, is also a journalist and has written articles for IWPR in which he accused senior public figures, including an MP, of atrocities, including murders. He said: "Of course we are all very worried about my brother. What has happened to him is very unjust. He has not committed blasphemy and he was not even allowed to have a legal defence. and what took place was a secret trial." Qayoum Baabak, the editor of Jahan-i-Naw, said a senior prosecutor in Mazar-i-Sharif, Hafiz Khaliqyar, had warned journalists that they would be punished if they protested against the death sentence passed on Mr Kambaksh. Jean MacKenzie, country director for IWPR, said: "We feel very strongly that this is designed to put pressure on Pervez's brother, Yaqub, who has done some of the hardest-hitting pieces outlining abuses by some very powerful commanders." Rahimullah Samander, the president of the Afghan Independent Journalists' Association, said: "This is unfair, this is illegal. He just printed a copy of something and looked at it and read it. How can we believe in this 'democracy' if we can't even read, we can't even study? We are asking Mr Karzai to quash the death sentence before it is too late." The circumstances surrounding the conviction of Mr Kambaksh are also being viewed as a further attempt to claw back the rights gained by women since the overthrow of the Taliban. The most prominent female MP, Malalai Joya, has been suspended after criticising her male colleagues. Under the Afghan constitution, say legal experts, Mr Kambaksh has the right to appeal to the country's supreme court. Some senior clerics maintain, however, that since he has been convicted under religious laws, the supreme court should not bring secular interpretations to the case. Mr Karzai has the right to intervene and pardon Mr Kambaksh. However, even if he is freed, it would be hard for the student to escape retribution in a country where fundamentalists and warlords are increasingly in the ascendancy.

Afghan reporters: Between a rock and a hard placeFebruary 2008. Afghan journalists live and breathe their country's dream of a better future. But they also live under the shadow of its violent past. In a country where the rule of law is fragile at best and where violence speaks volumes, the reporting of uncomfortable truths is often met with painful and unchecked consequences. In June last year, Zakia Zaki, a female broadcaster, died after being shot seven times in the face and chest as she lay sleeping with her eight-month-old son. Her mentor, Jamila Mujahed, still receives threatening letters and phone calls. Ms Mujahed, who champions women's rights through the Malalai Women's Magazine and the Voice of Afghan Women radio service, said: "They were naming my children. I am a journalist, but I am also a mother. "The voices are always different, always men. But the accents are from all over. I believe it's people who are afraid of independent media and women's rights." The government was outraged by Ms Zaki's murder and promised a huge investigation to bring her killers to justice. But six journalists were murdered in Afghanistan last year and all of the killers are at large. Ms Zaki owned a radio station called Peace Radio. She had openly criticised the warlords who hold sway in Afghanistan. The family of Sayed Pervez Kambaksh, the student journalist sentenced to death for downloading an article about women's rights, believe he was targeted because his brother, who is also a journalist, had offended the local governor. Afghanistan's warlords are so powerful, and the government's mandate is so weak, that the administration is often forced to make them ministers, senators, generals or governors to secure their loyalty, or at least stall their plotting. Even then, their allegiance is only as deep as the income their status allows them to generate from bribes and illegal deals. Yet warlords and commanders are just one of the groups that pose a constant threat to the free press. Afghan journalists must also report on a government which, at every level, is not used to criticism, but still happy to use its Soviet- trained secret police, the NDS, to mete out beatings and implement arrests. The government and the warlords have both been known to play the Islamic card to invoke support from religious conservatives. One agency reporter said he was held outside the Presidential Palace by a secret policemen who, moments earlier, had given him permission to interview a hunger striker. Haji Habib Rahman Ibrahimi, who writes for Afghanistan's main news wire, has also been threatened by a prominent MP and the Interior Ministry. He said: "I wrote a story about an MP's brother. He was a police commander, but he was arrested for armed robbery, kidnap and murder. The police didn't think I would write it. Even my boss didn't think I would. But I am a journalist." The story was splashed across Afghanistan's newspapers, and the journalist insists the intimidation was inevitable. He said: "The Ministry of Interior called me. They wanted to know who I was spying for. They accused me of destroying Afghanistan and insulting the mujahedin." More recently, a delegation of television executives was held overnight at the NDS headquarters after a meeting turned sour. They were only released when an Afghan TV chief cut a deal with President Karzai not to air an interview claiming two notorious government officials were corrupt. But the government says the free press is flourishing. Naji Manalai, an aide to the Culture minister, admitted there were problems, but said: "Everyone is learning. Six years ago we did not have a single free newspaper. Today we have 16 TV stations, 50 radio stations and more than 500 written publications." But Zia Bumia, president of the Committee to Protect Afghan Journalists, said that attacks on the media had increased by 15 per cent this year. And Zaid Mohseni, who owns a television company, said: "What we have is systematic intimidation resulting in self-censorship. We have to be very careful how we report the news."

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||