|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Smoking in Canada: Statistics, Laws and Cancer Prevention

One in Five Canadians still SmokeCanada - 19% of adult Canadians (age 15 or older) smoke regularly or socially according to Statistics Canada, a statistic which has stayed stable from 2005 to 2007. Average daily consumption per smoker is down to 15.5 cigarettes each, down by 25 per cent from 20.6 compared to 1985. Over the long term Canadian's have seen a decline overall in smoking, but prevalency is still high amongst youth (15 to 19 years old: 15%, down from 18% in 2005) and young adults (20 to 24 years old: 25%, down from 26% in 2005 and 33% in 2000), largely due to strong contraband and smuggling operations. Teenagers can buy a carton of 200 cigarettes for as little as $6, whereas in a convenience store it would cost $70. In 1965 49% of Canadians (age 15 or older) smoked. That number dropped to 46% by 1970, 44% by 1975, 38% by 1981, 32% by 1986, 31% by 1991, 29% by 1996, 24% by 2000, 23% in 2001, 22 % in 2003, 20% in 2004, and is currently plateaued at 19% from 2005 until 2007. Women still smoke less than men, but the gap is disappearing. 18% for females and 20% for males. Females smokers also smoke an average of 3.3 cigarettes/day less than males. Average daily consumption is 17% for males and 13.7% for females.

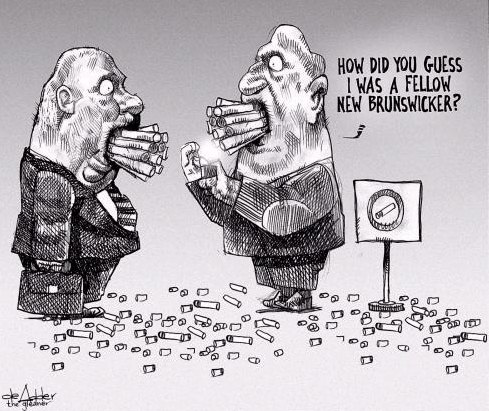

Provincially the lowest rate was in British Columbia, where only 16% of the population smoked. The highest was Saskatchewan with 24%. Saskatchewan also had the highest percentage of teenagers who smoke at 22%. New Brunswick has the dubious honour of chain smoking the most cigarettes/person (17.3 per day) while 21% of the population smokes. 14% of Canadian households report having at least one person in their home smoking every day or almost every day. 42% of Canadians who have a smoker in their homes or who allowed people to smoke in their homes say they place restrictions on taking a puff inside, indicating there is an increase in public awareness of the dangers of second-hand smoke. More homes are being made smoke-free, even those with smokers. 87% of Canadian smokers say they have smoking restrictions at their work place, requiring them to leave the building or company vehicle to have a cigarette. 6.2% report being able to smoke in a designated "smokers lounge" room in the building. 52% of Canadian smokers in all age groups said they did not attempt to butt out in the previous 12 months (down from 54% in 2000). 13% have tried to quit at least four times in the previous 12 months. Statistics Canada: The survey collected data from about 20,900 respondents between February and December 2007. The margin of error for the smoking rate for Canada is plus or minus one per cent, 19 times out of 20. A new survey is currently being conducted for 2008.

Health Care Costs in CanadaSmoking is still the number one preventable cause of death and disease in Canada. Each year over 45 000 Canadians die from tobacco-related causes. Some of these people never used tobacco--they were exposed to second-hand smoke. (According to the 2004 CTUMS, 15% of Canadian children from birth through 17 years of age are still regularly exposed to Environmental Tobacco Smoke.) While the emotional and social impact on the families involved cannot be measured, the economic cost to our health care system can be estimated, and it is significant. Over the years, there have been discussions about the calculation of smoking-related mortality rates. However, even if different methods of calculation are used, the bottom line is that a substantial number of preventable deaths occur every year. Note: One type of mortality that is not included in these numbers is death from fires started by smoking. While these deaths may be few each year, they too are preventable. Contrary to popular belief "lung cancer" is not the biggest killer of smokers and people regularly exposed to second hand smoke. Its a combination of cancers, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and even pediatric diseases caused by smoking mothers. Cancers: 38.6% (lung cancer is 29.3%).

Perhaps the most alarming number is the pediatric diseases/SAM, which is children killed by smoking-caused birth defects, pediatric heart disease/lung cancer, low birth weight and respiratory problems. The Canadian government spends $3 billion/year on smoking related health care and the Canadian economy loses $12 billion/year due to absenteeism and lost income due to premature deaths. Tobacco taxes account for approx. $2.5 billion. Evidently if tobacco taxes and medical bills were to be balanced out, tobacco taxes would have to be increased an additional 17%, to say nothing of the economic effects of tobacco draining the Canadian economy. Health Canada has a goal of lowering smoking rates to 12 per cent by 2011.

Treatment in CanadaNicotine patches, pills and gum are commonplace, but Canada has also developed some rather unusual products and services for treating nicotine addiction. One is Smokeless Cigarettes, and the other is a new laser treatment originally developed in Great Britain. A new Regina business (Precision Laser Therapy) is offering laser treatments that work like acupuncture without the needles to stop smokers from lighting up. The low-powered laser activates endorphins, triggering a natural high and killing the urge to smoke and the physical cravings. According to laser treatment workers: "Many people at the end of this treatment can hardly get off the chair because you've elevated those endorphin levels and released those feel-good chemicals at the same time." Apparently laser treatment itself could be quite addictive. Treatment (regardless of method) tends to focus on replacing cigarettes with either a different source of nicotine or by providing a different source of endorphin release (including psychological releases such as sex, rollercoasters, scary movies, sports and anything else that produces endorphins).

Smoking Etiquette in Canada

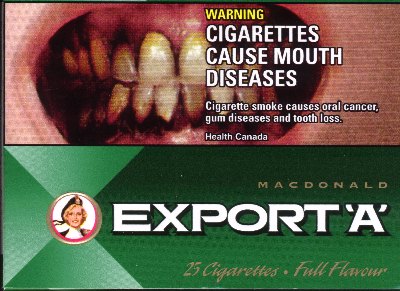

Anti-Smoking Campaigns in CanadaThere are numerous public and private smoking cessation programs in Canada. The Government of Canada legislated the mandatory display of warning messages on all cigarette packaging, including images depicting the long-term consequences of smoking, and has also banned tobacco advertising. A loophole which allowed the display of a sponsor's logo at cultural events (for example, the Symphony of Fire fireworks display, once known as the Benson & Hedges Symphony of Fire) was closed in the late 1990s. The Government of Ontario sponsors a program named Stupid, with an accompanying website stupid.ca, that seeks to educate adolescents about the danger of smoking. Through television, movie, print, and internet advertising, it informs people that they are much more likely to die from smoking than from certain obviously "stupid" activities, such as standing on a cliff during a lightning storm. The blue ribbon campaign was started in 1999 by the students at Hugh Boyd Secondary School in British Columbia and has been national now in Canada. In August 2008 the Government of Canada announced a $20 million investment in anti-tobacco activities, mostly aimed at getting rid of contraband tobacco smuggling in two key areas: strengthening tobacco control; and reducing the availability of illegal tobacco products in Canada. Taxing tobacco products is an important element of the governments' health strategy to discourage smoking among Canadians, but smuggling of contraband tobacco undermines this strategy and needs to be eradicated. In 2008 two of Canada's largest tobacco manufacturers (Imperial Tobacco Canada Ltd. and Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc.) admitted to deliberately “aiding persons to sell or be in possession of tobacco products manufactured in Canada that were not packaged and were not stamped in conformity with the Excise Act and its amendments and the ministerial regulations.”

Cigarette Smuggling in CanadaCigarette and other smoking product sales have been going down in recent years, but cigarette and tobacco smuggling is on the rise. Cigarette sales figures cannot be taken at face value. For example there was a sharp drop in reported cigarette sales between 1991 and 1993, during which period tobacco taxes were increased substantially and there was a huge increase in cigarette smuggling.

Counterfeit Cigarettes in CanadaCounterfeit cigarettes from China are not only illegal, but dangerous. Incidents have occurred in 2005 and 2007 where cigarettes have been found containing rat poison and a variety of other chemicals not normally found in cigarettes. Rivaling any one of the big multinational producers, China churns out 65% of the world's counterfeit cigarettes, a total of 35 billion cigarettes annually. Counterfeit Marlboros or Camels, or fake Virginia Slims may contain five times as much cadmium as genuine cigarettes, six times as much lead, and ten times as much poisonous arsenic. Cigarette counterfeiting is largely a clandestine cottage industry as many of China's small cigarette production facilities are quite literally underground, either in basements or in subterranean rooms accessible only by tunnels. Vancouver is the primary port of entrance for counterfeit cigarettes.

Tobacco Advertising in CanadaIn Canada, advertising of tobacco products has been prohibited by the Tobacco Products Control Act as of 1988 and all tobacco products must show attributed warning signs on all packaging. Immediately following the passing of the legislation through parliament, RJR-MacDonald (RJR-MacDonald Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General)) filed suit against the Government of Canada through the Quebec Superior Court. It was argued that the act, which originally called for unattributed warnings, was a violation of the right to free speech. In 1991, the Quebec Superior Court ruled in favour of the tobacco companies, deciding that the act violated their right to free speech under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as well as being ultra vires. The Crown subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. On September 21st, 1995 the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the Tobacco Products Control Act as legal, forcing the tobacco companies operating in Canada to print hazard warnings on all cigarette packs. However, the Court struck down the requirement that the health warnings be unattributed, as this requirement violated the right to free speech, further ruling that it was in the federal government's jurisdiction to pass such laws, as it fell under the peace, order and good government clause. Recently, sin taxes have been added to tobacco products, with the objective of decreasing usage by making the products less affordable. Currently, radio ads, television commercials, event sponsoring, promotional giveaways and other types of brand advertising are prohibited as well as in-store product displays. Until 2003, tobacco manufacturers got around this restriction by sponsoring cultural and sporting events, such as the Benson and Hedges Symphony of Fire (a fireworks display in Toronto and Vancouver), which allowed the manufacturers' names and logos to appear in advertisements sponsoring the events, and at the venues. The ban on tobacco sponsorship was a major factor that led to the near-cancellation of the Canadian Grand Prix in Montreal and the du Maurier Ltd Classic, a women's golf tournament on the LPGA tour (now known as the Canadian Women's Open). In May 2008, retail displays of cigarettes in convenience stores in Ontario and Quebec have been outlawed. They are now all hidden.

Smoking Bans in CanadaSmoking in workplaces, public places (airports, malls, etc.) is banned in all territories, provinces and in federally regulated buildings. Smoking rooms in public places and federal buildings are also banned. Most Canadians (82%) support a ban on smoking in vehicles with children under 18 years old, according to a poll released in August 2008 by the Canadian Cancer Society. According to the same poll 69% of smokers also support a ban against smoking in vehicles with children under 18 years old. Nova Scotia became the first province to pass legislation to ban smoking in vehicles with children under 19. Similar legislation is being proposed in other locations across Canada. Infants and children have smaller, immature immune systems and higher respiratory rates, which increases the risk of asthma, ear infection, sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory failure, heart disease and lung cancer. Newfoundland and Labrador: smoking has been banned in all public places, including bars and bingo halls, since 2005 under the province's Smoke-Free Environment Act. Prince Edward Island: banned smoking in public places and workplaces since 2003. Ventilated smoking rooms are allowed, however, but food cannot be served in them. Nova Scotia: From 1 December 2006 onwards, smoking is banned in public places, with the exception of special rooms in nursing homes and care facilities. Tobacco products cannot be displayed prominently in stores. From 1 April 2008, smoking in a car with passengers under 19 inside is illegal. New Brunswick: banned smoking in all public areas since October 2004 and does not allow specially ventilated rooms. Quebec: will eliminate designated smoking rooms and retail tobacco displays by 31 May 2008. There has been a comprehensive ban on smoking in public places, including bars and restaurants, since 2006. Ontario: will ban retail displays of tobacco in 2008. Since 2006, all workspaces and enclosed spaces open to the public ban smoking. Manitoba: The Non-Smoker's Health Protection Act has banned all smoking in public spaces since October 2004. Non-smoking areas, or specially ventilated rooms, are not allowed in bars and restaurants. Saskatchewan: reinstated 'shower curtain law' (2005) requires shop owners to keep tobacco sales out of sight. There are fines of up to $10 000 for violation of the Tobacco Control Act which bans smoking in all public areas, indoor and outdoor, including clubs for veterans. Alberta: has had a public smoking ban since 1 January 2008. The City of Calgary has legislated that bars and restaurants must be smoke free (since 2007); in the city of Edmonton there has been a smoking ban since 2005. British Columbia: B.C. has a smoking ban, passed in March 2007, bans smoking in all public spaces such as restaurants, pubs and private clubs, offices, malls, conference centres, sports arenas, community halls, government buildings and schools. The ban also applies to outdoor areas of restaurants and bars - so that even when sitting outside, people cannot smoke and no-one inhales their smoke. Nunavut: has banned smoking in public spaces since 1 May 2004, including bars. The Northwest Territories: banned smoking as of 1 May 2004, in all public places and workplaces, including restaurants, bars, bingo and bowling facilities, and casinos. The Yukon: implemented a smoking ban on 15 May 2008. It was the last of the provinces and territories to implement a ban.

Smoking in the USACigarette smoking has been identified as the most important source of preventable morbidity and premature mortality worldwide. Smoking-related diseases claim an estimated 438,000 American lives each year, including those affected indirectly, such as babies born prematurely due to prenatal maternal smoking and victims of "secondhand" exposure to tobacco's carcinogens. Smoking costs the United States over $167 billion each year in health-care costs including $92 billion in mortality-related productivity loses and $75 billion in direct medical expenditures or an average of $3,702 per adult smoker.1

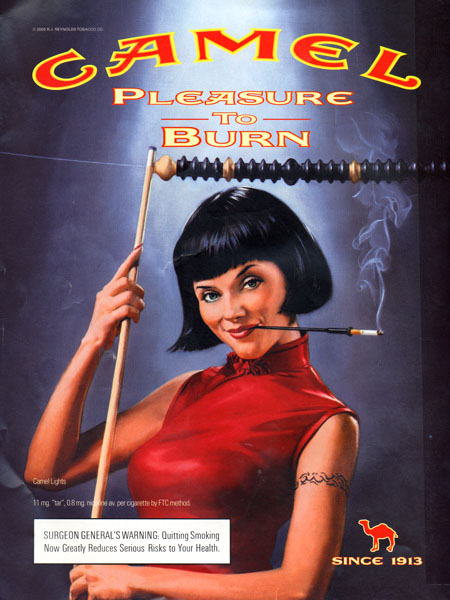

Tobacco Advertising in the USAIn the United States, in the 1950s and 1960s, cigarette brands were frequently sponsors of television programmes—most notably game shows such as To Tell the Truth and I've Got a Secret. One of the most famous television jingles of the era came from an advertisement for Winston cigarettes. The slogan "Winston tastes good like a cigarette should!" proved to be catchy, and is still quoted today. Another popular slogan from the 1960s was "Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!," which was used to advertise Tareyton cigarettes. In June 1967, the Federal Communications Commission ruled that programs broadcast on a television station that discussed smoking and health were insufficient to offset the effects of paid advertisements that were broadcast for five to ten minutes each day. "We hold that the fairness doctrine is applicable to such advertisements," the Commission said. The FCC decision, upheld by the courts, essentially required television stations to air anti-smoking advertisements at no cost to the organisations providing such advertisements. In April 1970, Congress passed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act banning the advertising of cigarettes on television and radio starting on January 2, 1971. The Virginia Slims brand was the last commercial shown, with "a 60-second revue from flapper to Female Lib", shown at 11:59 p.m. on January 1 during a break on The Tonight Show. Smokeless tobacco ads, on the other hand, remained on the air until a ban took effect on August 28, 1986. After 1971, most tobacco advertising was done in magazines, newspapers and on billboards. Since the introduction of the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act all packaging and advertisements must display a health warning from the Surgeon General. In November 2003, tobacco companies and magazine publishers agreed to cease the placement of advertisements in school library editions of four magazines with a large group of young readers (Time, People, Sports Illustrated and Newsweek). The first known advertisement was for the snuff and tobacco products of P. Lorillard and Company and was placed in the New York daily paper in 1789. Advertising was an emerging concept, and tobacco-related adverts were not seen as any different from those for other products: their negative impact on health was unknown at the time. Local and regional newspapers were used because of the small-scale production and transportation of these goods. The first real brand name to become known on a bigger scale was "Bull Durham" which emerged in 1868, with the advertising placing the emphasis on how easy it was "to roll your own". The development of colour lithography in the late 1870s allowed the companies to create attractive images to better present their products. This led to the printing of pictures onto the cigarette cards, previously only used to stiffen the packaging but now turned into an early marketing concept. Billboards are a major venue of cigarette advertising (10% of Michigan billboards advertised alcohol and tobacco, according to the Detroit Free Press). They made the news when, in the tobacco settlement of 1999, all cigarette billboards were replaced with anti-smoking messages. In a parody of the Marlboro Man, some billboards depicted cowboys riding on ranches with slogans like "Bob, I miss my lung". America's first regular television news programme, Camel News Caravan, was sponsored by Camel Cigarettes and featured an ashtray on the desk in front of the newscaster and the Camel logo behind him. The show ran from 1949 to 1956.

Statistical Sources

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||