|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Building Green Architecture

It’s Easy Building Green

We expanded and modernized our house 10 years ago, adding an entire second floor after having a couple of kids and reluctantly concluding we needed more space. We looked at moving but ultimately concluded we didn’t want to leave our waterside, dead-end-street neighborhood that was safe for kids and cats alike. In remodeling we wanted to do the right thing: We bought all energy-efficient and water-conserving appliances for kitchen and laundry. We installed a stove and range that also economize on energy, and kitchen cabinets made from sustainable wood. We even put recycled glass tile on the wall behind the stove counter and a reclaimed wood cutting board counter next to it. We hung drapes made from hemp and bought some new green-friendly furniture. That included sofas made from recycled soda bottles, deck chairs made of old milk cartons, and chairs made with removable, washable and replaceable slipcovers. We also installed wood floors made from reclaimed pallets, retrofitted much of the house with compact fluorescent bulbs, and installed skylights to minimize daytime lighting needs. And throughout the house we used non-toxic, water-based paints.

Though it was only a decade ago, none of this was easy to do at a time when many of the sources available were either overseas firms or nascent American companies struggling to survive. Our kitchen cabinets came from Germany and the dishwasher was Swedish. The company that provided the reclaimed pallets sold us the last of its stock and then went belly-up. And the maker of the soda pop bottle-upholstered couches didn’t stay in business for long, either. I regret that we didn’t incorporate even more green features into our redesign. We could have gone solar with rooftop photovoltaic collectors to heat our water, or chosen an on-demand, tankless heater to replace the dinosaur we took out. For that matter we could have implemented a whole host of energy-efficient and resource-saving features had we more time to spend on it or a green building industry as robust then as it is today. Of course, we can retrofit some of these innovations, and probably will. Indeed, green-friendly materials and appliances have come down significantly in price since we were plying our modest attempt at an “eco-home” in the 1990s. There are also now innumerable resources available to architects, builders and do-it-yourselfers, aided in large part by the growth of the Internet. Green superstores such as the Environmental Home Center in Seattle and Green Building Supply in Iowa, among many others, will ship anywhere. Hundreds of informational websites, such as BuildingGreen.com, offer detailed listings for thousands of environmentally preferable building products and offer tips on green building and remodeling. There are also a number of helpful books. There is even a natural handyman network (naturalhandyman.com) that will find you professionals who know the ABCs of green building. And today many states have grant programs that can help offset the costs of energy-efficiency improvements, and there are federal tax credits to be had as well. As the weather gets colder and many of us batten down for winter, it’s a great time to start drawing up plans for those improvements you’ve been contemplating. Go green and you can make an important individual contribution to the environment, help take a bite out of global warming, and save money over the long haul, too.

The Global View: Sometimes, Small is Beautiful

As the construction industry “goes global,” the amazing diversity of the world’s architecture has suffered. In the last 30 to 50 years, new buildings in New York, London and Beijing have started to look the same. Green building designs, by contrast, embrace differences, including cultural biases and local ecological issues. Because it casts off the “one size fits all” mantra, green construction has been better at listening to and adapting from local concerns.

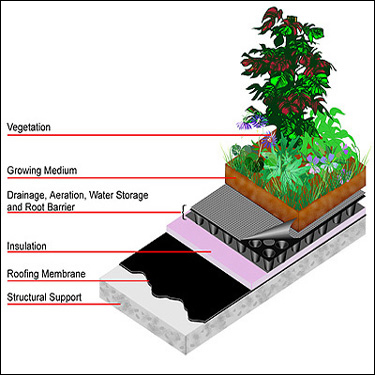

Europe Sets the Standards German green builders are leading the world in the design and construction of green roofs, which capture and store huge amounts of water that would otherwise increase flooding. According to Greenroofs.org, these living structures capture 70 to 90 percent of the rainwater that falls during the summer months. Over 12 percent of all flat roofs in Germany are now green roofs, and the green roof industry in Germany is growing 15 percent per year. To combat pollution from coal-burning power plants, which have caused widespread allergy problems and acid rain, German engineers have designed building-integrated photovoltaics to capture solar energy and reduce coal energy use. The German Mont-Cenis Academy features the world’s largest roof-integrated photovoltaic system, which produces electricity at 2.5 times the building’s consumption. In addition, the Passivhaus-Institut in Darm-stadt provides rigorous, voluntary standards for ultra-low energy buildings. There are now more than 6,000 Passive House buildings in Europe. “The Netherlands is very concerned about global warming,” says Kirsten Ritchie, director of environmental claims for Scientific Certification Systems. “Much of the country is below sea level or just above it. Almost of necessity, the Dutch have become leaders in energy efficiency, renewable energy sources and urban planning.” In the Netherlands, government buildings, universities and banks have taken the lead in green building. Britain, too, has been a leader in green building. In fact, Britain’s environmental assessment system for buildings, BREEAM, was the first in the world. It has also been the most successfully embraced rating system, used to assess 20 to 25 percent of new buildings in England. Most of the push for green building in Britain has been from the government through regulations, tax incentives and support for research. Like the Nether-lands, Britain’s major green buildings are mostly governmental and university buildings, including the offices of the Parliament and the University Library in Coventry.

Adaptations in Asia The cultural influence on green building in Japan is evident in a singular focus on the health of indoor environments. Japan’s sustainable building assessment system, similar to LEED, was developed by the Japan Sustainable Building Consortium (JSBC). Japan has concentrated on assessing buildings for the quality of their indoor environments. Not surprisingly, this concern has propelled Japan to develop super-efficient, high-tech climate control systems that improve indoor air quality. Greg Franta, an architect and team leader with the Rocky Mountain Institute Built Environment Team, says Japan’s green thinking runs deep. “In both energy and materials efficiency, Japan has been remarkably creative,” he says. Japan has a population density 10 times that of the U.S., does not have any significant oil supply and is the world’s largest timber importer, so energy and material efficiency are crucial. With the world’s largest population and its highest coal consumption, it’s imperative that China strive for sustainability. David Rousseau, a senior associate of the International Centre for Sustainable Cities and the principal of Archemy Consulting, says China is making progress. Rousseau most recently built an energy-efficient student dorm in Jinan, the capital of Shandong Province. With virtually all of Shandong’s electricity from coal, the Shandong Institute of Architecture and Engineering asked Rousseau to design a sustainable experimental building. Rousseau and ICSC designed living quarters that are 75 percent solar powered, use a quarter of the energy of standard Chinese construction and are livable year round, thanks to superior insulation and ventilation. Venture capital is rare in China, so the projects require government funding. Rousseau says there was very little green thinking in China 15 years ago, but now the government’s position is shifting. “They’re still reluctant to admit their policies are wrong, or may be harming the citizens,” he said, “but many of their newer regulations indicate they now recognize the need to turn back urban sprawl and reduce greenhouse emissions... and their ability to mobilize is unparalleled.”

The Curitiba Model In many Third World nations, green building has yet to gain traction. While there are pockets of progress, the movements in Latin America, Africa and India are still embryonic. There are few governmental regulations, and enforcement of what regulations do exist is often lax. Also, since most green buildings require a higher initial investment that is recouped over several years, few Third World communities can wait for the payback. And even fewer corporations in developing nations are worried about sustainable buildings. Another hurdle is that standards developed in wealthier countries are seldom applicable in the Third World. Even in industrialized nations, green buildings tend to be demonstration projects rather than the norm. In the UK, for instance, only 25 percent of buildings are BREEAM certified. According to Franta, the most successful Third World projects are “large in scale and community based,” and often “learn from [the developed world’s] mistakes by avoiding paths that have caused problems for us.” This is evident in Curitiba, Brazil, one of the world’s most successful examples of sustainable urban planning and building. Architect Jaime Lerner, former mayor and president of Curitiba’s Research and Urban Planning Institute, realized that to create a sustainable city he needed not only energy-efficient buildings, but site selection that respects green space, effective and affordable transportation, innovative zoning, solid waste and wastewater management, and well-thought-out education programs. According to Jonas Rabinovitch, the city’s international relations coordinator, Curitiba has achieved a 95 percent literacy rate. Some 99.5 percent of households have good quality drinking water and electricity, and 83 percent of the population has a high school education. The most effective green building work uses Curitiba as a model, taking local resources, climate, culture and population into account. Many developing nations are following this diverse, localized approach to green building, while the U.S. and Europe follow a different, but no less useful, path.

Green Roofing Materials and Benefits

By Charles Moffat There are basically two types of green roofs you can put on a home or even a commercial structure. 1. The first is simply using modern materials that are green / eco-friendly and cause no impact to the environment during the process of making the roofing tiles, bricks, etc. This typically costs more on the outset, as such materials are usually more expensive. However the added the quality of green roofing materials means that the roof will last a lot longer than a traditional tar and shingle roof. As such there is a growing and more popular business in green roofing materials as people realize that such roofs last longer, save people more money over the longer term, are better insulated - and the fact that they don't harm the environment during the process is a nice bonus. Companies like Joe Hall Roofing are becoming experts in the green roofing industry and offer a variety of residential and commercial roofing styles. 2. The second type of green roofing is the kind whereby you turn your roof into a garden, which means rebuilding the structure of the roof to allow drainage of water. There are three ways to do this:

Honestly, in my opinion, I don't see why many structures in urban environments don't have an entire green house on the roof. The city of Toronto could be providing most of its own vegetables this way as there is ample unused roofs that are basically just wasted space. There are numerous benefits (financial and environmental) of having green roofs. It is a wonder that more people don't make the effort to invest and cultivate this as a worthy opportunity.

Green Design on a Roll

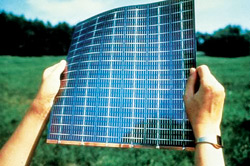

Lindsay Suter, a green architect in Connecticut, made a vow. He wasn’t going to design mega mansions or outsized additions. Instead, he was going to devote 100 percent of his practice to environmentally themed designs. It’s a promise he kept. Suter lives in a 220-year-old former grain mill next to a dammed river in North Branford, with solar panels on the roof. He admits that leaf-shaded Connecticut river valleys are not necessarily the best place for photovoltaics (PV), but he’s been stymied in the green home project he’d most like to see realized: hydroelectric power. “Every time I look outside at the dam I see four or five kilowatts going over the top,” he says. The regulations that have held up Suter’s hydroelectric project are the same ones that prevent a lot of destructive development in wetlands. But the old ways of doing things tend to slow down what would otherwise be a full-fledged green design revolution. Many of the concepts have been around for decades, even before the first Earth Day in 1970, but new design improvements and price reductions for green materials (coupled with the high cost of fuel) have made green design practical and cost-effective. John Rountree calls himself a solar architect, but his projects in that field were few and far between in the 1990s, when systems were expensive and required a lengthy wait for return on investment. Today, Connecticut-based Westport Solar Consultants is thriving, partly because photovoltaics have come of age, and partly because the utility-funded Clean Energy Fund was created by the state legislature, with a $21 million budget for residential renewable projects. For solar, homeowners can receive awards of $5 per installed watt (up to a $25,000 maximum), which effectively means they can offset half the cost of installing PV. And there’s a $2,000 federal tax credit, too. “Global warming has become a household word, thanks in part to Al Gore’s movie An Inconvenient Truth,” says Rountree. “A few years ago green design work was three percent of my business; now it’s 20 percent. People want solar on their existing houses, or an addition with solar integrated into it.” And incorporating solar is easier than ever, because six companies now make roof-integrated PV systems that do away with unsightly freestanding panels. Two of Rountree’s clients have also installed home-based geothermal systems. “The people who do these projects are highly educated, and they understand the ramifications of high energy use,” Rountree says. “Their motivation is largely environmental, because there’s still no immediate payback.”

Colleges have also become hotbeds of green design, generating interest in a new crop of consumers. David W. Orr is director of the Environmental Studies Program at Oberlin College in Ohio and author of Design on the Edge: The Making of a High-Performance Building (MIT Press). The college practices what it preaches, having just completed a cutting-edge green building, the Adam Joseph Lewis Center. Designing the building was a 10-year effort, led by some of the premier thinkers in the field, including architect William McDonough, energy guru Amory Lovins and closed-loop “living system” pioneer John Todd. “There wasn’t the integrated design expertise in any one firm,” Orr says, “so we put together an all-star team.” The solar-powered building pro-cesses all its own wastewater through Todd’s Living Machine, incorporates recycled and reused materials, and is surrounded by native plant gardens. The two solar installations, 59 kilowatts on the roof and 100 on the ground, generate 30 percent more power than the building can use. Because Ohio is a “net metering” state, Oberlin can sell its excess electricity back to the grid to offset its expenses. “We can build high-performance buildings at very near the cost of regular buildings, so the payback is very quick,” Orr says. He adds that because it was “the first substantially green building on a college campus,” the project brought out donors who had never previously given to Oberlin.

It’s not surprising that the Oberlin project lasted a decade, because zoning laws and building departments are not yet oriented to the green approach. “There are minefields, bombs at every turn,” says Suter. “You can always tell the innovators, because they have the most knives in their backs.” It’s not just colleges that can benefit. A new study from the American Institute of Architects and Capital E, “Greening America’s Schools,” concludes that “making over” a school building saves an average of $100,000 a year in operating costs, enough to hire two new full-time teachers. And, of course, green design and alternative energy systems have their limitations. The National Association of Home Builders says the average home was 2,300 square feet in 2005, up from 1,400 square feet in 1970. Some towns and cities have minimum area requirements, making it nearly impossible to build a very small home. But while McMansions are common around the country, some sport many green features. “It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to put a small solar system in a 10,000-square-foot house,” says Rountree. “People have a love affair with big houses and big cars, but the low-hanging fruit is reducing the size of the house.” Suter advises his clients to “get the loads down” (electric and heating costs, and even commuting times) “before we start talking about neat things like geothermal and PV.” Green design is losing its isolation, with alliances between the human-scale land-use planners known as New Urbanists and progressive architects. “We’re trying to strengthen the connection,” says John Norquist, former mayor of Milwaukee (1998 to 2003) and current president of the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU). “New Urbanists tends to be obsessed with mixed-use zoning and smaller roads, not necessarily energy efficiency.”

CNU is working with the U.S. Green Building Council (GBC) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) to create the first set of standards for what NRDC calls “building environmentally responsible neighborhoods.” The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design-Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) standards administered by GBC to certify green buildings will incorporate smart growth principles. A green building might lose a point in the ratings because it is situated a long way away from any public transportation system, explains Norquist. A new neighborhood-oriented development that won points for mixed-use buildings and traffic-calmed streets would get more for having a green building on site. Don Chen, executive director of Smart Growth America, says that “green building is essential to sustainable development, but it’s not enough. Green buildings need to be located in a green manner as well, located close to public transportation and convenient destinations.” Chen points to a study by the Jonathan Rose Companies, concluding that a family living in an average urban town house is actually living more sustainably than a comparable suburban family in a “green” building with a Toyota Prius in the driveway. Green design, it seems, is a holistic concept.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||