|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farming Demographics and Intercropping

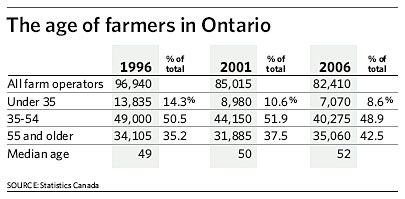

Young people are being driven off the farmBy Emily Salzburg - November 2007. When I was growing up it didn't even occur to me that I would someday be making a choice: Living in the city, or living in the country. Even though I had come from generations of farmers who had moved to Canada well over a hundred years ago, the idea of me farming was as ridiculous as being an astronaut. It just wasn't my thing, and frankly I don't think my parents enjoyed it either. They were constantly in poor financial shape. Why would ANYONE want to be a farmer in this day and age? The government ignores you, the food industry pays crap-effing-all and people look down on you even though you are providing a public service by filling their bellies. These days the farming industry is becoming... industrialized. When young Kurtis Andrews walks into his family's barn, he can't just ask one of the employees where his dad is. He has to ask for "Mr. Andrews." That's because few of the market staff know Kurtis anymore. They think he's another customer. Andrews spent 20 years working on the family farm. When he was seven, he bought a bicycle with the money he'd saved weeding the fields by hand for $1 an hour. He's climbed the trees, built a swimming raft for the irrigation pond, and rumbled across the fields on a tractor. But now he's a stranger on his parents' family farm. "It feels odd," says Andrews, 34, examining a 20-year-old family photograph that hangs in the barn. In it, he, his two sisters and their folks pose in a raspberry field, each of them dressed in red-and-white checkered shirts and holding a basket of berries. It's full of joy and optimism – hardly the picture of farming today. Andrews is no longer a country boy. He lives six hours away in Ottawa, the capitol of Canada, where he's in his second year of law school, and he has no plans to return to the fields. Same goes for many ex-farmers. The statistics are blatantly clear – young people are leaving farming in droves. In Ontario the number of farm operators aged 35 and under plunged by 35 per cent between 1996 and 2001. Since then, it's dropped another 21 per cent. Only 8.6 per cent of farmers are in that age group today. Enrolment in agricultural colleges is plummeting. And the average age of the Ontario farmer keeps creeping up. Around Toronto, it's now 53. When they retire, will there be anyone left farming the land? It's what Wally Seccombe calls a "generation impasse." He is the founder and chair of Everdale, an organic farm near Orangeville that trains young farmers. "If we want to be farming in Ontario in 20 years," he says, "we have to find a new generation who are not the sons and daughters of farmers and get them recruited on the land and farming in a very different way than we have before." You don't have to dig deep to get to the roots of the problem. At its base are simple economics: for the most part, farming isn't a lucrative business anymore. Around Toronto, most farms make less than a junior child-care worker – under $25,000 a year. Not enough to support a family.

Global Warming and DroughtsNo thanks to global warming farmers are suffering more droughts and low crop yields. It just isn't raining enough, and that is harming the amount of cash farmers earn. To survive, almost half of Ontario farmers work second jobs. With increased competition from places such as China and South Africa, it's harder to make a living wage. "There's no money now," says Greg Downey, a 33-year-old who started working full-time on the family farm near Brampton 13 years ago, when the business was "more profitable." It's a decision he still questions, watching his bricklaying and banking brothers padding their bank accounts. "If I was going back to college now, I wouldn't be coming home," he says. "I'd get into a trade." The lifestyle doesn't help either. There are few days off and fewer vacations, due to monetary reasons and sheer logistics. Dairy cattle have to be milked twice a day, regardless of your baseball tickets or dinner date. When Cecelia McMorrow was a child, members of her family used to take turns racing back to the farm every day while on vacation at a nearby cottage. "Every day of my life, every social function, I had to leave at 4 p.m.," says McMorrow, 26, who, despite being president of the Junior Farmers Association of Ontario, has no intentions of farming herself. "That's not a commitment I want to make." She works for the Lindsay Agricultural Society but dreams of working in international development. Her parents, like many in the industry, encouraged her to go to university and study something other than agriculture. Farmers, like factory workers and taxi drivers, have bigger dreams for their children. "The idea of farming as an exciting, viable, respectable profession doesn't exist now," says Christie Young, director of FarmStart, a Guelph non-profit organization bent on reversing the trend. Even the few who do go into agriculture studies at university rarely return to the land. The majority land more secure agribusiness jobs, like working as a lab technician for a pesticide company or selling tractors for John Deere. "The education system is not pushing people into farming," says Dave Lewington, 30, past youth president of the National Farmers Union. "It's grooming young people for jobs in agribusiness." In high school, his guidance counsellor dismissed his plans to farm as "a waste of good marks," he says. He did it anyway, buying a spread near Sudbury, where land is still affordable, in 2004. Which brings us to the overwhelming roadblock for the aspiring farmers who don't inherit an operation: land prices. Buying a farm around Toronto is like to buying a mansion in Forest Hill. Around the Andrews' farm near Milton, farmland is being scooped up by developers at $50,000 an acre. A 100-acre farm will sell for $5 million – and that's not including the tractors (a new one can cost as much as $250,000), irrigation pipes, seed and other necessities. Few people under 35 have saved up $125,000 for a down payment, especially if they've been working, and getting experience, on a farm. "Really, you'd have to win the lottery to get into farming (near Toronto)," says McMorrow. "For most people, that's not how they want to spend their winnings." Renting land from a developer can be cheap. But it's risky. Andrews was growing winter wheat and corn on a nearby field and was kicked off without notice so the developer could build a driving range. Without any security, it's hard to build up a business. Plus, it's not easy to find farmland to rent that comes with a barn and a house. "There needs to be some perks to farming," says one young farmer. "You should at least have the joy of waking up on the farm." There is a minority of young farmers swimming against the current. Many of those who don't inherit the business are drawn to farming for environmental reasons. They're what Seccombe dubs the "modern-day back-to-the-landers." Most are working on small-scale operations, growing organic food directly for specific customers. They're part of a new type of farming, called "relationship-farming," that's at the heart of the local food movement. A just-released survey of alumni of a local organic farming program called Collaborative Regional Alliance for Farmer Training (CRAFT) revealed that most were young females who grew up in the city. They're people like Tarrah Young, who sees farming as environmental activism. She just bought 50 acres near Ayton, an hour northwest of Guelph, where she plans to raise organic pigs and turkeys. "I feel I can make a change, even if it's only on 50 acres," says Young, 30. "I'm helping create a better model for food production and help people create better health." She could only afford the farm with help from her parents. And, she expects to depend on her partner's earnings as a graphic designer to pay the mortgage. She reckons that in due time, she will be able to pay herself around $25,000 a year. That makes her the exception. In the CRAFT survey of intern alumni, only 36 per cent were still farming – most tilling small plots (five acres and less) and not making a living off it. It raises the question: as a society, are we going to rely on idealism to feed us, along with the sacrifices of a few Thoreau-types willing to live on peanuts? It seems hardly a model food policy. Where you add up all the pros and cons of farming it is no wonder people are choosing to live in the city and learning a new way to make money.

Intercropping: These farmers CAN see the forest for the treesA farming practice that results in better soil, more earthworms, much higher capture of carbon dioxide, less nitrogen runoff, more birds and insects, and double the crop yield in drought years – it sounds too good to be true. Yet this is exactly what experiments at Guelph University are suggesting. The most astonishing conclusion is that if farmers adopted the practice throughout the 455,000 square kilometres of marginal or degraded land currently being farmed, Canada could come within a hair's breadth of meeting its Kyoto commitment with an 18.6 per cent reduction in the nation's CO2 emissions. The practice is called intercropping – planting crops between rows of trees. At Guelph, the rows of trees are 12.5 metres to 15 metres apart, and this year the crop is soybeans. The experiments have been going on for several years, using different crops and the results have been compared to identical crops grown in open fields. Andrew Gordon, professor of forest ecology and agroforestry, has been supervising the experiments, assisted by Naresh Thevathasan, manager of agroforestry research and development at the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph. Thevathasan explains that the trees take up about 10 per cent of the intercropped area. Yet in drought years, the yield has been double that in the open area, because the trees helped retain moisture in the ground. In normal and wet years, the yield in the actual growing areas has been identical, but because of the space taken by trees, the yield for the total area, trees included, has been about 10 per cent lower. Accompanied by two graduate students, Thevathasan gave me a tour. The soybean plants were ripening to a buttery yellow and a row of poplars stretched as far as I could see over a gentle rise. The trunks were a good 40 centimetres across at hip height and the trees were roughly 13 metres high. Fast-growing poplars can reach this size in 12 years, Thevathasan says. A couple of years ago, some were sold for $100 to $150 a tree.

In this experiment, he adds, there are 111 trees per hectare. They can be used to make plywood, low-quality lumber, chipboard, pulpwood, even pellets for heating. They also produce a lot of leaves each year, which are shed where the crops are planted, making the soil richer in organic matter. Earthworms in the leaf litter number 125 to a square metre, compared with two worms per square metre in the open field. Ten different kinds of birds foraged in the intercropped area, Thevathasan says, compared to four in the open area. In addition, there were a lot more parasitic insects in the intercropped area, which might be good news for pest management. Nitrogen added to the soil through decomposing leaves reduced significantly the amount of fertilizer required for crops. And, says Thevathasan, leaching of nitrates from the soil, which causes nutrient overloading in waterways, was reduced by 50 per cent in intercropped areas, because tree roots take up nitrogen. It was Rachelle Clinch, one of the graduate students, who put her finger firmly on the issue raised by the experiments. "We haven't changed our thinking about agriculture since North America was colonized," she said. "It's always been focused on clearing land to grow crops, with no place for trees. "If only we would learn to use trees to help farming, instead of seeing them as a hindrance, we'd see many, many benefits."

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||