|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Disaster Capitalism in the United States

War Profiteerism

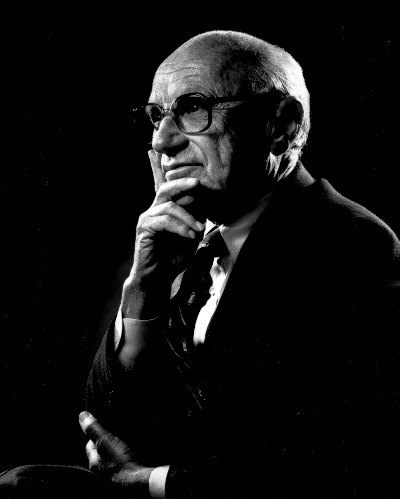

By David Suma - 2008 Naomi Klein’s concepts of “disaster capitalism” has been evident across the globe in countries like Russia, Chile, Poland, and China, but more importantly, in disaster capitalism’s country of origin, the United States of America. In her book, “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism”, Klein defines “disaster capitalism” as orchestrated raids on the public sphere in the wake of catastrophic events, combined with the treatment of disasters as exciting market opportunities (Klein 6). The concept centres around the ideology of Milton Friedman, who proclaimed that only a crisis, actual or perceived, produces real change. Friedman was a Nobel Prize winning economist who believed that the idea of a free market in a capitalist society would initially help us achieve absolute individual freedom. To exemplify, Klein uses the Hurricane Katrina catastrophe in her introduction as an example of how Chicago School ideologists like Milton Friedman use disaster capitalism to exploit a large scale shock or crisis. Klein argues that even an event as catastrophic as 9/11 can be used as “shock treatment” to help disorient and confuse the public and wage a profitable, privatized war like the War in Iraq. However, the radical change that has been implemented through this ideology has had significant effects on the public sphere within the United States, not to mention many other countries around the world. In order to understand the reasoning behind “disaster capitalism”, it is important to be aware of what former President Dwight Eisenhower called the “military-industrial complex”. In his farewell address to the nation, Eisenhower warned the public about the vast implications of the military-industrial complex. He stated, “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes” (Eisenhower). Unfortunately, what Eisenhower feared has now become a reality. The military-industrial complex can be defined as a coalition consisting of the military and industrialists who profit by manufacturing arms and selling them to the government. It signifies a comfortable relationship between parties that are responsible for managing wars (the military, the presidential administration and congress) and companies that produce weapons and equipment for war (the industry). To put it simply, the Military-Industrial Complex is a relationship that may develop between defence contractors and government forces, where both sides receive what they are perceivably looking for: a successful military engagement for those planning the war and financial profit for the corporations involved. In other words, it is basically a “war for profit” theory. This idea of “war for profit” is nothing new as history certainly shows. It can be traced back centuries earlier where Empires were driven by arms races, especially those between the European powers of France, Spain and Britain, which are all basically more primitive versions of the military-industrial complex. The idea was that a country must build up and maintain a strong military in order to be considered a world power. Centuries ago, militaries like this were needed to protect themselves against the possible invasion of neighbouring countries. These days, it is ridiculous to consider an invasion against the United States of America. However, the U.S. is one of the only nations in the world that significantly relies on the military-industrial complex. It is without a doubt that the defence industry profits most when a country wages war overseas. The United States clearly doesn’t take any risks when it comes to warfare, thus, they spend ridiculous amounts of money on their military. To sum up, war is definitely good business for the companies who invest in it, including manufacturing, servicing, production, etc. To the United States, a war based economy fuelled by the military-industrial complex is just as profitable as any other stable, growing economy, where tanks, planes and ammunition maintain superiority over the production of more traditional goods and products. To date, there are a large number of corporations that currently hold defence contracts with the United States government with the largest being Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Blackwater, Kellogg Brown & Root, and the Raytheon Company. Lockheed Martin holds the biggest contract totalling just over 5 billion U.S. dollars (Defense Contracts). Since Eisenhower’s infamous farewell speech, the United States has invaded a vast number of countries including Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, Grenada, Panama, Bosnia, and more recently, Iraq.

Considering the influential concept of the military-industrial complex, it is important to bear in mind its relationship with the now more apparent disaster capitalism complex, as Klein describes it. Klein begins to describe the beginning of its structuring in the U.S. by focusing her attention mainly on political figures Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and of course, George W. Bush. Klein defines the “disaster capitalism complex” as having much farther reaching tentacles than the military-industrial complex that Eisenhower warned against at the end of his presidency. It is global war fought on every level by private companies whose involvement is paid for with public money, with the unending mandate of protecting the United States homeland in perpetuity while eliminating all “evil” abroad (Klein 14). She explains how the Bush administration has outsourced the most sensitive and core functions of the government from providing healthcare to soldiers, interrogating prisoners, and gathering information on U.S. citizens. Not only that, but even the service sector has begun reaping the benefits of the disaster capitalism complex. Maintaining the U.S. military is now one of the fastest-growing serviced economies in the world. Despite the horrifying realities of disaster capitalism, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Although this dispicable form of shock therapy has been proven effective against the American public, it is only temporary. The longer this “War in Iraq” continues, the more the American public is going to question its motives, as they are beginning to do so already. According to Klein, shock eventually wears off, and people will become well oriented and conscious. It is important for people to realize and understand what exactly is going on. People are already beginning to stop waiting for the government to come around and help, and they are instead taking the initiative as they should be doing. In times of crisis, we must question certain actions of the government, as well as take action. We must go back to our morals and values and focus on what is right, instead of what is considered to be “profitable” or “economical”.

President Dwight Eisenhower's Farewell Address to the NationJanuary 17th 1961.

Good evening, my fellow Americans: First, I should like to express my gratitude to the radio and television networks for the opportunity they have given me over the years to bring reports and messages to our nation. My special thanks go to them for the opportunity of addressing you this evening.

Three days from now, after a half century of service of our country, I shall lay down the responsibilities of office as, in traditional and solemn ceremony, the authority of the Presidency is vested in my successor.

This evening I come to you with a message of leave-taking and farewell, and to share a few final thoughts with you, my countrymen.

Like every other citizen, I wish the new President, and all who will labor with him, Godspeed. I pray that the coming years will be blessed with peace and prosperity for all.

Our people expect their President and the Congress to find essential agreement on questions of great moment, the wise resolution of which will better shape the future of the nation.

My own relations with Congress, which began on a remote and tenuous basis when, long ago, a member of the Senate appointed me to West Point, have since ranged to the intimate during the war and immediate post-war period, and finally to the mutually interdependent during these past eight years.

In this final relationship, the Congress and the Administration have, on most vital issues, cooperated well, to serve the nation well rather than mere partisanship, and so have assured that the business of the nation should go forward. So my official relationship with Congress ends in a feeling on my part, of gratitude that we have been able to do so much together.

We now stand ten years past the midpoint of a century that has witnessed four major wars among great nations. Three of these involved our own country. Despite these holocausts America is today the strongest, the most influential and most productive nation in the world. Understandably proud of this pre-eminence, we yet realize that America's leadership and prestige depend, not merely upon our unmatched material progress, riches and military strength, but on how we use our power in the interests of world peace and human betterment.

Throughout America's adventure in free government, such basic purposes have been to keep the peace; to foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among peoples and among nations.

To strive for less would be unworthy of a free and religious people.

Any failure traceable to arrogance or our lack of comprehension or readiness to sacrifice would inflict upon us a grievous hurt, both at home and abroad.

Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by the conflict now engulfing the world. It commands our whole attention, absorbs our very beings. We face a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. Unhappily the danger it poses promises to be of indefinite duration. To meet it successfully, there is called for, not so much the emotional and transitory sacrifices of crisis, but rather those which enable us to carry forward steadily, surely, and without complaint the burdens of a prolonged and complex struggle – with liberty the stake. Only thus shall we remain, despite every provocation, on our charted course toward permanent peace and human betterment.

Crises there will continue to be. In meeting them, whether foreign or domestic, great or small, there is a recurring temptation to feel that some spectacular and costly action could become the miraculous solution to all current difficulties. A huge increase in the newer elements of our defenses; development of unrealistic programs to cure every ill in agriculture; a dramatic expansion in basic and applied research – these and many other possibilities, each possibly promising in itself, may be suggested as the only way to the road we wish to travel.

But each proposal must be weighed in light of a broader consideration; the need to maintain balance in and among national programs – balance between the private and the public economy, balance between the cost and hoped for advantages – balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable; balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual; balance between the actions of the moment and the national welfare of the future. Good judgment seeks balance and progress; lack of it eventually finds imbalance and frustration.

The record of many decades stands as proof that our people and their Government have, in the main, understood these truths and have responded to them well in the face of threat and stress.

But threats, new in kind or degree, constantly arise.

Of these, I mention two only.

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction.

Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence – economic, political, even spiritual – is felt in every city, every Statehouse, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central, it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present – and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system – ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society's future, we – you and I, and our government – must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without asking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be, instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.

Such a confederation must be one of equals. The weakest must come to the conference table with the same confidence as do we, protected as we are by our moral, economic, and military strength. That table, though scarred by many past frustrations, cannot be abandoned for the certain agony of the battlefield.

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose differences, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war – as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years – I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.

Happily, I can say that war has been avoided. Steady progress toward our ultimate goal has been made. But, so much remains to be done. As a private citizen, I shall never cease to do what little I can to help the world advance along that road.

So – in this my last good night to you as your President – I thank you for the many opportunities you have given me for public service in war and peace. I trust that in that service you find some things worthy; as for the rest of it, I know you will find ways to improve performance in the future.

You and I – my fellow citizens – need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nations' great goals.

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing aspiration:

We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Now, on Friday noon, I am to become a private citizen. I am proud to do so. I look forward to it.

Thank you, and good night.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||